Most-Favored-Nations and the Warped Curve

The uneven consequences of most-favored-nations (MFN) pricing

I did a double-take seeing last week’s Economist article on the most-favored-nations (MFN) pricing policy. This policy was announced via Executive Order by the Trump administration in May.

It’s not every day that international drug pricing makes its way into The Economist!

Today, we’ll spend some time unpacking MFN and playing out what could happen if it were implemented.

But First, a Little Background

As far as I can tell, the nitty-gritty details of how (and if!) MFN would be implemented are still up in the air.1 But generally, MFN would cap US branded drug prices at the lowest price found in peer countries for the same product.2

The Trump administration has been very public in its stance that other countries are “freeloading” off the American healthcare system, and that MFN is a way to make others pay their fair share for drugs and innovation.

Pharmaceutical trade groups have publicly opposed MFN as a threat to innovation.3 Academics have argued that MFN would abdicate decision-making to foreign governments, and that the US should develop its own drug value and pricing rules.

Many have warned that MFN would limit and delay access to new medications outside of the US.

MFN’s Uneven Impact: Three Scenarios

Setting aside the uncertainty around how (and if!) MFN would be implemented, it’s worth playing out how this policy could impact drug prices, market access, and drug development incentives.

To do this, let’s consider three drugs with different profiles:

Commodity (with generic competition)

Medical breakthrough

Incremental improvement

For this thought experiment, we’ll keep things high-level and gloss over the many nuances of ex-US drug pricing and market access. We’ll also make a few simplifying assumptions:

MFN only applies to new drug launches

France is the reference country

List prices are referenced (no confidential rebates or discounts)

MFN applies to branded drugs that don’t have generic or biosimilar competition4

Commodity

For branded me-too drugs with generic or biosimilar comparators, it’s unlikely that MFN would create big changes. These products are typically priced at generic levels in countries like France, and these markets are increasingly skipped by manufacturers in this situation.

MFN might formally exclude these therapies from consideration, but if not, launching at generic prices would only risk pulling down US revenues. The net effect would be marginal, with manufacturers opting for a few more skipped launches in ex-US countries.

Drugs with this profile are US-focused today and would remain so under MFN.

Medical Breakthrough

For true breakthroughs (say, a curative therapy for pancreatic cancer), MFN would strengthen manufacturers’ leverage abroad.

For example, if France’s CEPS set too low a price,5 companies would face a binary choice: accept it and risk US revenues, or walk away. With US sales on the line, the threat of walking away would become much more credible.

At the same time, countries like France face intense pressure to provide timely access to medical breakthroughs. That political urgency, combined with manufacturers’ stronger bargaining position, would likely push prices higher.

Whether this would result in higher global revenues would depend on the magnitude of ex-US price increases versus US price decreases. The net effect would likely range from neutral to positive.

Since ex-US countries spend less of their GDP on drugs,6 any new spending on breakthrough therapies would require: 1) higher overall drug budgets (slow, resisted), 2) cuts to other social spending (politically hard), and/or 3) less spending on other drugs (most likely - see Incremental Improvement).

Incremental Improvement

MFN would present the most challenges for drugs that are better than standard of care (but not game changers) and benchmarked to branded comparators.

Today, such therapies often launch in markets like France at prices close to incumbents (but still well below US levels). Some health systems reimburse them for their incremental benefits, others do not.

With MFN, however, these lower prices would flow back into the US market, making ex-US launches less attractive. At the same time, governments facing higher costs for breakthrough therapies - but unwilling to expand overall drug budgets - would be even less likely to pay for incremental improvements.

The likely outcome for these drugs would be manufacturers opting to delay or forego access in ex-US markets. In some scenarios, this could even push manufacturers to raise drug prices in the US to make up for lost revenues.

Reduced access to these therapies would directly impact patients. Treatment responses can vary due to patient genetics, comorbidities, tolerability, and other factors - the ‘incremental’ drug with minimal average benefit might be the only effective option for thousands of patients.

The Warped Curve and Pharma’s Response

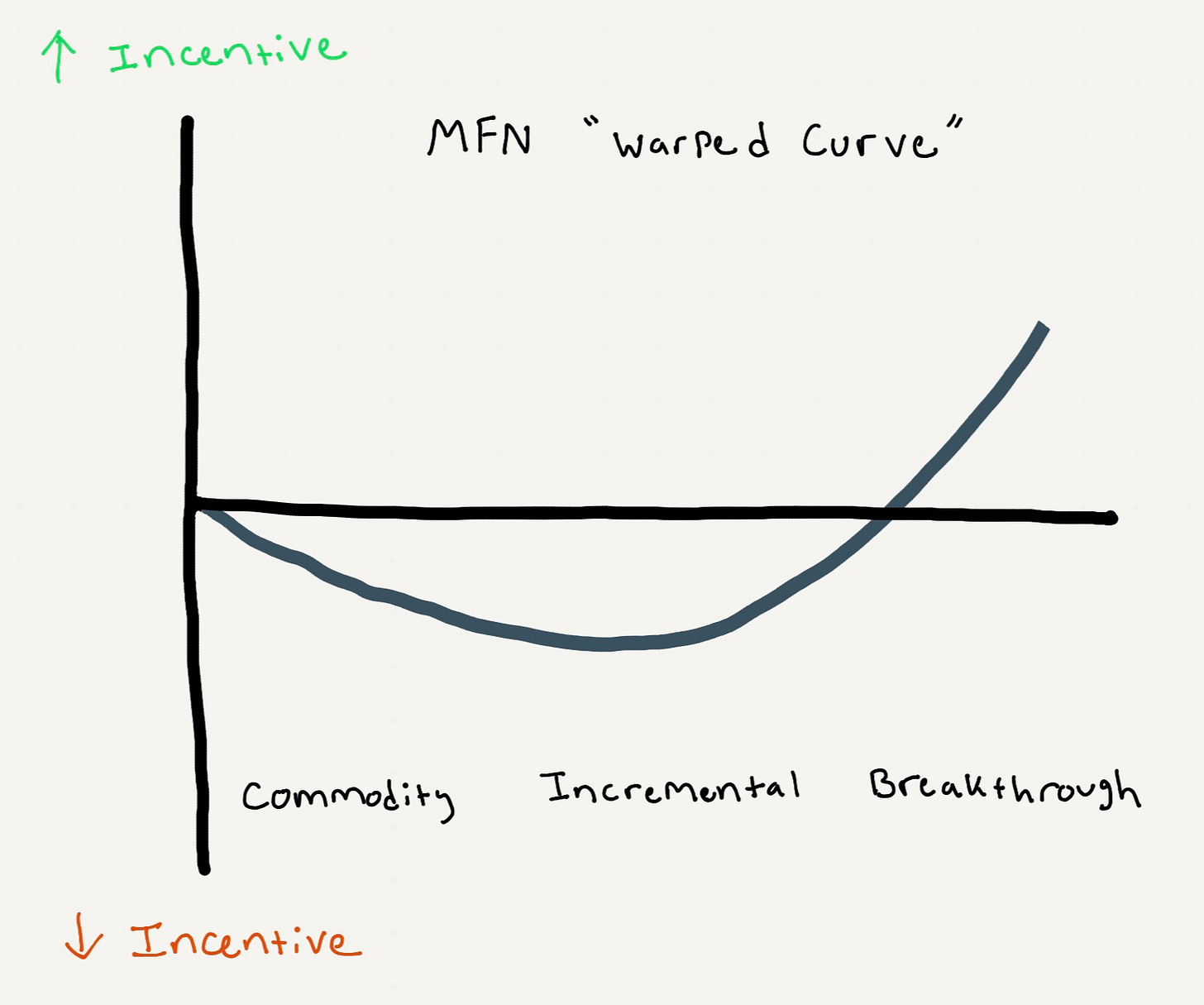

In a normal market, we’d expect drug development incentives to rise steadily from commodity drugs, to incremental improvements, to breakthroughs.

MFN would bend that logic via a “warped curve” (see figure). Incentives would be unchanged for commodity drugs, reduced for incremental improvements, and increased for breakthroughs.

That distortion would force companies to rethink several development and commercialization strategies. Among these shifts, one likely response would be increased focus on precision-targeting for drugs in ex-US markets.

By using diagnostics, AI tools, and clinical decision algorithms, these manufacturers could position “incremental” therapies as breakthroughs for specific patient subgroups - such as cancer patients identified through biomarker testing.

This strategy would lead to narrower market access (i.e., smaller patient populations) in ex-US markets, but at premium prices that don’t erode US revenues.

Teams responsible for pricing, access, and evidence generation would need to engage much earlier in development to shape trial design and subgroup strategies. Geographic launch sequencing would become even more strategic and interdependent.

There would also be more incentive to monitor ex-US real-world drug utilization and prevent drift into lower-value populations that could trigger re-evaluations and costly price cuts that flow back to the US.

Finally, MFN would also alter licensing strategies. Small biotechs often out-license ex-US rights to larger firms with market access infrastructure. With ex-US prices feeding back into US revenues, those deals would become riskier with more complex contingencies. That added friction could slow licensing and early-stage investment.

Key Takeaways

MFN would create distinctly different outcomes depending on the drug.

Breakthrough therapies would gain leverage, likely commanding higher prices in ex-US countries. Incremental improvements would face the worst economics, with many manufacturers opting to delay or forego ex-US markets entirely. Things wouldn’t change much for me-too drugs with generic competition.

This dynamic would alter the risk-reward calculation of pharmaceutical R&D - breakthrough innovations and precision-targeted therapies would become more attractive, while broader incremental improvements would become less attractive.

Some drugs would see higher international prices, but at the cost of reduced therapeutic diversity and patient choice.

There are many outstanding questions about how MFN would work in practice, including:

Which patients would MFN apply to? All patients (e.g., both commercially- and publicly-insured) or just publicly-insured patients? MFN-related letters sent to pharmaceutical companies in July only focused on Medicaid patients

Which drugs will MFN pricing apply to? Per HHS: “HHS expects each manufacturer to commit to aligning US pricing for all brand products across all markets that do not currently have generic or biosimilar competition with the lowest price of a set of economic peer countries.” Would this apply to all drugs or just newly-launched drugs? Will “generic and biosimilar competition” be defined at the molecular level, or more broadly at the indication level?

Which countries would be referenced for MFN pricing? HHS has announced that the MFN target price will be “the lowest price in an OECD country with a GDP per capita of at least 60 percent of the U.S. GDP per capita.” What data sources and methods will be used to calculate GDP per capita in each country?

Which price(s) would be used for MFN pricing? Drugs often have publicly-disclosed “list prices” (sticker prices), as well as confidential “net prices” that reflect discounts and other rebates. Would MFN be based on list or net prices?

How would MFN interact with existing pricing laws and programs? Would MFN prices supersede negotiated prices from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)? Would MFN prices impact the 340B drug pricing program? Medicaid best price?

Per Bloomberg, there have also been hints that a new federal website will be introduced to help patients directly purchase drugs from manufacturers at MFN prices, bypassing pharmacy benefit managers:

The proposed website would allow patients to search for specific medicines and be connected with platforms that sell them […] Officials have discussed creating a Trump brand for the website, with “TrumpRx” one name that’s been considered

This stance is echoed by the author of the The Economist article (Tomas Philipson):

Of course, if [the MFN] cap were implemented without European prices being lifted, biopharma innovators would suffer such steep falls in revenue that they would have to shut down R&D projects. That would have global consequences, including for America

The definition of “competition” that would apply under MFN remains unclear. For our thought experiment, we’ll assume that MFN excludes situations where drugs are benchmarked to generic comparators in peer countries

In France, the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), through its Transparency Commission (CT), assigns an Amélioration du Service Médical Rendu (ASMR) rating to new drugs based on their added clinical benefit versus comparators. The ASMR rating guides price negotiations with the Comité Économique des Produits de Santé (CEPS)

According to EY/PhRMA (2025), 2023 spending on new innovative medicines (defined as all new active substances approved by FDA, EMA, or Japan’s PMDA and first launched globally between 2014 and 2023) equalled ~0.8% of per-capita GDP in the US, compared to ~0.5% in Italy and Spain, 0.4% in Japan and Germany, and 0.3% in Canada and France